Scripture Readings (Twenty-Second Sunday in Ordinary Time, August 29, 2021)

What does it mean to be a “law-abiding” Christian? In other homilies, we’ve talked about the Law of Moses quite a lot. By this time, we should understand that the Law of Moses was presented to Israel as the stipulations of the covenant between Yahweh and God’s people. We might think that Moses went up Mount Sinai and came back down with the Torah in its entirety. Is that what happened? When we take a closer look at the history of the people of Israel and the history of the Hebrew Scriptures in particular, this understanding becomes untenable. The Law of Moses is far from a monolithic entity. There are the stipulations we know of as the Ten Commandments. There are laws governing worship and sacrifice. There are laws regulating money and trade. There are laws touching on interpersonal relations like marriage, slavery, the treatment of widows and orphans, strangers, and foreigners. Then there are the dietary laws and the determination of the ritually pure and impure.

As usually happens when we dig into the Scriptures, to understand their meaning, we have to get rid of certain common misconceptions that distort our view of them. The Torah could not have been given to Moses as is. Most scholars date the exodus event around the year 1450 BC. The Torah as we know it—the first five books of our Bible—was composed almost a thousand years later, most of it between the seventh and fifth centuries BC, although pieces of it can be dated much earlier, to the tenth century BC, during the reign of King David and Solomon when the written Hebrew language first came into existence. The originals of these fragments have been long lost. The Torah was composed between the Babylonian Exile, and the restoration of Israel under King Darius of Persia.

Evidently, since the Law of Moses had no single date, it also had no single source. It’s a compilation of governmental ordinances, religious rubrics, and health codes. Despite what we read in today’s first reading about Moses saying, “…you shall not add to what I command you nor subtract from it,” throughout its history, groups of reformers have done just that. They’ve added to it and applied interpretations to it that made its stipulations even more stringent and specific. We can see a perfect example of this in today’s gospel, where the Pharisees complained, “Why do your disciples not follow the tradition of the elders but instead eat a meal with unclean hands?” There is no such stipulation in the Torah. It was just a popular hygienic practice that the Pharisees turned into an obligation.

That’s how legalism grows. The ancient Israelites understood this. Remember Adam and Eve in Genesis? In Genesis Chapter 2[16-17], God is quoted as saying to the man, “’You are free to eat from any of the trees of the garden except the tree of knowledge of good and evil. From that tree you shall not eat; the moment you eat from it you are surely doomed to die.’” There’s the law. Now, here’s the interpretation. “The serpent asked the woman, ‘Did God really tell you not to eat from any of the trees in the garden?’ The woman answered the serpent: ‘We may eat of the fruit of the trees in the garden; it is only about the fruit of the tree in the middle of the garden that God said, “You shall not eat it or touch it, lest you die.”’” [Genesis 3:1-3] Really? Did God say anything about touching the fruit?

All laws, whether they’re in the Torah or in a country’s body of legislation and ordinances, have the same purpose: to train people to do the right thing until they understand the reasoning behind the law. Think of laws as ethical training wheels. Training wheels serve a good purpose when you’re learning to ride a bike, at least until the rider has mastered the skill. But riding on your own can be scary. Accidents can and do happen. Yet, what would it be like if a cyclist not only refused to take off the training wheels, but also added extra ones to make it more even difficult to fall—and then tried to make everyone else do the same?

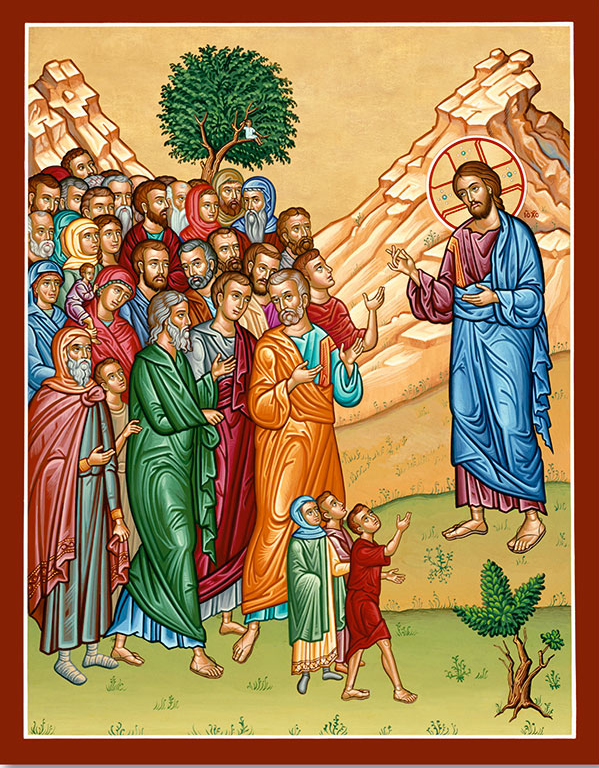

That’s the Pharisees in today’s gospel are trying to do: make everyone afraid of breaking the law. They assume that, if slavishly following the Law of Moses makes you a good person, then failing to follow it makes you evil. That’s why they were criticizing Jesus’s disciples, and, by extension, criticizing Jesus for allowing it. Jesus’s answer to them was to show them how wrong their premise was. Following the law—even the Torah—cannot make you a good person. You don’t go to heaven for following the rules, or to hell for breaking them. What makes you a good person is what’s inside you, motivating your actions. For Jesus, that’s the love you have in your heart and mind and soul and strength for God and for one another. What’s within you creates for you your heaven or hell.

The more spiritual you are, the more conscious contact you have with God, the more mindful you become—the more religious you are—the less hold any laws will have on you. You will instinctively know what the right thing to do is by following the law of love in your heart, and you will do it. To paraphrase Saint Paul from today’s second reading, “Religion that is pure and undefiled before God the Father is this: to care for orphans and widows, immigrants, refugees and the homeless in their affliction, and to keep oneself unstained by the world of wealth, power and prestige.”

We, the followers of Christ, have been freed from the yoke of the law. We are no longer bound by it because we have been called to a deeper obedience, offering ourselves to the Father as Jesus offered himself on the cross for all humankind. Saint Augustine, whose feast we celebrated just yesterday [August 28], distilled the obedience of the Christian to Christ’s law of love into just one sentence. He said, “Love, and do what you will.”