Scripture Readings

The story is told about the scene at the Last Judgment. All the good people of the world are standing in a long line, waiting impatiently for their turn at God’s judgment seat, but the line isn’t moving. People are calling out, “What’s going on up there?” and, “Why the hold-up?” After a very long time, a murmur is heard, being passed along down the line from the front saying, “They’re letting those other people in, too!” People start shouting, “That’s not fair!” and, “After all I went through? How dare you!” and, “I’m not sharing my eternity with them!” And people yelled and stomped their feet and shook their fists in the air, and, at that instant, they were damned…because that was the Last Judgment.

In Jesus’s time, scholars of the Law were concerned about doing what was necessary to be a good and righteous person. Some, like the Pharisees, taught that obedience to every single tenet of the Law was essential. If you broke one commandment, or one part of a commandment, you broke the whole Law. Others, like the Scribe in today’s Gospel, tried to distill the Law down to its basic essentials, in other words, what simple tenet could one adopt as a way of life and fulfill the whole Law. That’s why the Scribe asked Jesus to tell him which was the greatest commandment.

Jesus answered by quoting the Shema—שְׁמַע יִשְׂרָאֵל יְהוָה אֱלֹהֵינוּ יְהוָה אֶחָֽד—the passage from Deuteronomy we heard in today’s first reading—a passage that was recited at every temple service, every synagogue service and every prayer service in the Jewish home. It is, in effect, the Creed of Judaism. “Hear, O Israel! Yahweh is our God, Yahweh alone! Therefore, you shall love Yahweh, your God, with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your strength. Take to heart these words which I enjoin on you today.” But he didn’t stop there. He went on to quote a passage from Leviticus [9:18]: “Do not seek revenge or bear a grudge against anyone among your people but love your neighbor as yourself. I am Yahweh.” Then Jesus linked the two passages together to form the distilled essence of the “Law and the Prophets,” in other words, what we today call the Hebrew Bible.

Going deeper, we can say that these two tenets are, in fact, just two aspects of the same reality. In his first letter, Saint John [4:20] provides us with a commentary on this commandment when he writes, “Whoever claims to love God, yet hates his brother or sister is a liar. For whoever does not love their brother and sister, whom they have seen, cannot love God, whom they have not seen.”

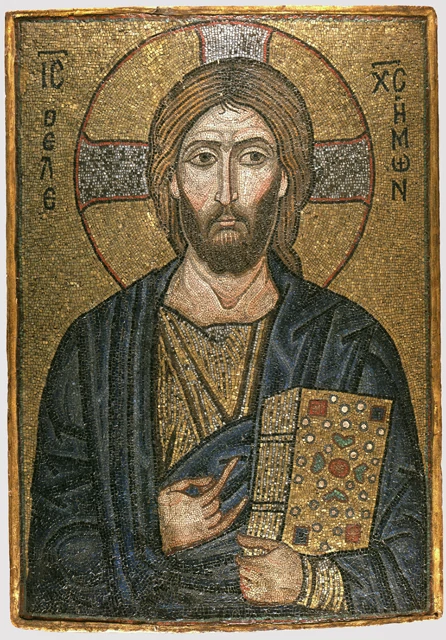

We are invited to see the image of God in our fellows. The book of Genesis [2:27] says, “God created humankind in his image; in the divine image he created them.” What is this “image of God,”—the famous “imago Dei” in Latin, the εικων του Θεου (eikōn tou theou) in Greek, the צלם־יהוה (tselem-Yahweh) in Hebrew? It’s God’s shadow, his reflection, his likeness as creator and ruler. Obviously, that doesn’t mean that God looks like you and me. What it does mean is that when we see the best of humanity, we’re seeing a reflection of God. That’s why Jesus could say to Philip in Saint John’s gospel [14:9], “Have I been with you all this time…, and yet you still don’t know who I am? Whoever has seen me has seen the Father.” Now, what happens when we push that moment forward all the way to the crucifixion? The dirty, bruised, bloody, nailed body of Jesus on the cross is still the imago Dei, the image of God.

We can’t hope to see the image of God in our fellow human beings with our physical eyes, any more than the bystanders could see God in the crucified Christ. It takes spiritual eyes—the eyes of faith—that can look beyond the superficial to see the deeper spiritual realities. Jung called it the “collective unconscious.” It’s the living core, the deepest and best part of our personalities that we share with one another as a species.

Tragically, it is possible to snuff out the life of that core by destructive fundamental life choices. It is possible to smash the imago Dei and render it unrecognizable. For us, the observers, it doesn’t mean that we’re free to hate either the “sinner” or the “sin.” It should give us cause to mourn—to mourn the loss of goodness and beauty in a brother or sister, to mourn the obscuring of the imago Dei in a soul created to shine like the sun. What should we do, then, when we encounter one of these people in whom our spiritual eyes can no longer find any trace of that divine spark? We cannot hate them. There is only one thing we can do to fulfill the greatest commandment to love God and one another, that is: we can keep looking.

Our Church teaches that hell exists. You also know that the Church also recognizes that certain people whose lives have been exemplary are now in heaven. As a matter of fact, we celebrate all of them in the Feast of All Saints (November 1). But never in the entire history of its existence has the Christian Church ever officially declared that any individual—including Judas Iscariot—is condemned to hell. Why? Because, as tiny as the image of God may be in some people who have done terrible, unthinkable things, only God knows whether that spark of his life has been extinguished or not.

Keep the great commandment. If you “love the Lord your God with all your heart, with all your soul, with all your mind, and with all your strength,” then you will never give up looking for the image of God in everyone you encounter. And should you ever find yourself in that long line at the Last Judgment, and you hear that those others are going into heaven with you, too, then rejoice, because God could still see in them something you might have missed.

Get articles from H. Les Brown delivered to your email inbox.