Scripture Readings

Every choice demands that we make a value judgment on our respective options. Whether instinctively or through reasoning, we weigh the positives against the negatives, because even though every choice provides us with something, it nonetheless costs us something. To receive a return, we must always make an investment. Our job is to decide which option provides the greatest return for the least investment. Isn’t that how it works? We need to know our return on investment—our ROI.

The scribes in today’s gospel were looking for their ROI. Who were they? Scribes were literate—they could both read and write at a time when most people could not, they were learned in the details of the Scriptures, particularly the Torah, and they were also the people who painstakingly made copies of the Scriptures, faithful to the last detail. They had obviously spent much time and effort studying to gain proficiency in their work and their understanding of what they read and wrote. This was a rather remarkable achievement considering that, at the time of Jesus, only about fifteen percent of the population could read. People relied on the scribes to read the Scriptures to them and explain them, therefore they were in great demand and greatly honored. They were addressed as “Rabbi.” or “Teacher” or “Master” out of respect.

Although Jesus was not from a wealthy or high-status family, he could read. In the Gospel of Luke [4:16-17], we find, “When he stood up to read, the scroll of the prophet Isaiah was handed to him.” Those who addressed him often called him “Rabbi” or “Teacher” or “Master,” although he frequently declined those titles of respect.

Yes, the scribes had their titles of respect. That’s not strange. We, too, give titles to show respect to those who have earned advanced degrees, whether MDs or PhDs, and we call them “doctor,” which, by the way, is simply the Latin word for “teacher.” The scribes of Jesus’s time enjoyed their titles of respect, and they went even farther. They were used to claiming a privileged place in the synagogue—a bench facing the congregation was placed in front of the Ark where the Torah was kept. And they exaggerated their symbols of religious practice: the phylacteries they wore on their foreheads and arms and the tallit prayer shawls they wore on their shoulders. When asked to lead prayer, it was common for them to offer long and involved prayers to show their devotion. Their public piety became so ostentatious that people were expected to bow profoundly when they passed by, even in the marketplace. The scribes had made an investment in their professions, and they expected a return.

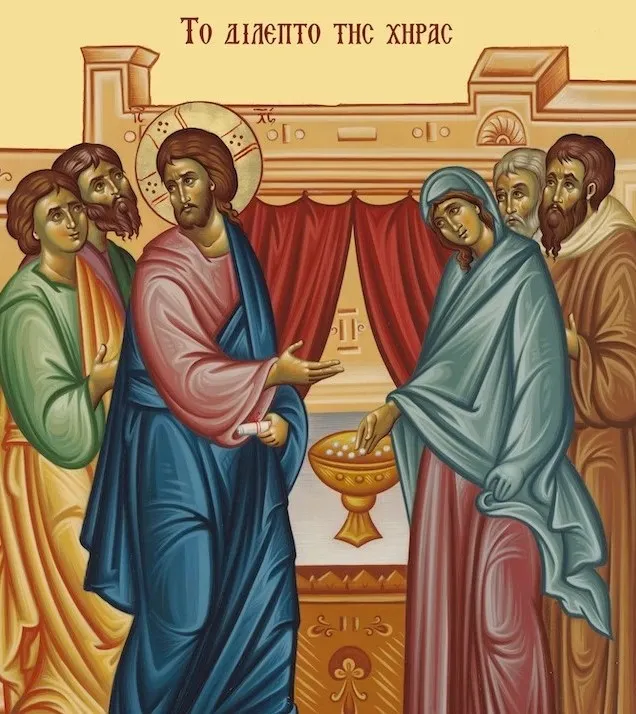

In the gospel, Jesus contrasts the pomposity of the scribes with the widow who put a couple of small coins into the collection box. Was he pointing to her humility in contrast to the arrogance of the scribes? Perhaps. Was he comparing her generosity to the self-seeking of the scribes? Certainly, he was. However most importantly, he was turning the scribes’ ROI on its head. You see, the woman was not seeking a return on her investment at all. Her generosity had nothing to do with expecting praise from those around her, nor even expecting a quid pro quo from God. She wasn’t thinking, “If I put this much in, God is sure to give me XYZ.” What she was doing was completely different. Her generosity came from a sense of gratitude. It’s that sense that we find in Psalm 116 [:12-13] when it says, “What return can I make to the Lord for all he has given me?”

Gratitude is a kind of spiritual cure-all. It heals what ails us spiritually. When we are in gratitude—that is, recognizing our indebtedness to God for all we have and all we are—it’s impossible at the same time to act arrogantly with pomposity and grandiosity in front of others. We can’t boast and, at the same time, recognize our indebtedness. Gratitude drives home to us how foolish we’d sound to shout out in front of everyone, “Look at me! I’m in debt!”

So, the widow dropped her two coins into the collection box out of gratitude rather than arrogance. But there’s yet another dimension to gratitude that we see in her. You can’t be grateful and, at the same time, feel sorry for yourself. The woman could not possibly have given all she had to live on if she had seen her life as misery and thought of herself as a victim simply because she was poor.

Gratitude shows itself in generosity. It doesn’t have to be money. It can be time. It can be attention. It can be acts of kindness. It can be patience. It can be understanding. It can be forbearance… Is this starting to sound familiar? Are you hearing echoes of Saint Paul’s first letter to the Corinthians, perhaps?

Love is patient, love is kind. It is not jealous, [love] is not pompous, it is not inflated it is not rude, it does not seek its own interests, it is not quick-tempered, it does not brood over injury, it does not rejoice over wrongdoing but rejoices with the truth. It bears all things, believes all things, hopes all things, endures all things.

I Corinthians 13:4-7

There you have it. Gratitude is the litmus test for the whole of our spiritual lives. It’s the remedy for both arrogance and self-pity. It’s the indicator gauge of our capacity to love. As we quickly approach the end of our liturgical year, we’re going to be hearing about the end of the world and the Last Judgment. When it’s our turn, I doubt we’ll be shown a set of scales with our good deeds on one side and our sins on the other. Instead, I think we’ll get to look into a mystical mirror that allows us to see the depth and breadth of our gratitude. If we had the opportunity to look into that mirror today, what would we see?

Get articles from H. Les Brown delivered to your email inbox.

What’s Happening i’m new to this, I stumbled upon this I’ve found It absolutely useful and it has aided me out loads. I hope to contribute & help other users like its helped me. Great job.