Scripture Readings

The gospel today poses many problems. Even Scripture scholars far more learned than I admit that it’s a head-scratcher. Here, I’ll do my best to dissipate some of the fog, but there’s no guarantee that it’ll ever be crystal clear. What we have here is a parable of Jesus—the parable of the unjust steward—with no less than four attempts to explain it tacked on to the end. The parable itself ends at verse eight: “And the master commended that dishonest steward for acting prudently.” That’s where I’d like to stop—at least for now.

Let’s examine the background of the parable. Who was the steward, what was his function, and why was he there? The territory of Israel—including Judah and Galilee—was dotted with large farms worked by tenant farmers, some with large orchards and others with vast fields with crops like wheat. Many of these farms were owned by absentee landowners. Not only did slaves work the land, but they were also in charge of administering it. Stewards were slaves who oftentimes grew up on the property and were entrusted by the landowners with the duty of managing the property, overseeing the growth and distribution of the produce, and assuring a profitable return on investment for the owner.

Stewards had something in common with tax collectors—that is, they were required to turn over a certain amount of income, but whatever they could gain above and beyond the requirements they got to keep for themselves. What often happened—then as now—was that the tenant farmers wouldn’t have enough capital to afford to plant or harvest their crops, so they would borrow what they needed from the landowner’s estate and pay it back in produce—with interest—after the harvest. They would sign a promissory note with the steward for the amount that they owed. The steward would set the interest. A dishonest steward could charge usurious interest because that went directly into his pocket, and the tenant farmers of the land would have no choice but to pay it…something like our student loans today.

So, how did the dishonest steward in the parable squander his master’s property? It seems as though the master wasn’t receiving the profits he required from his landholdings while the steward was growing increasingly wealthy. Evidently, he was looking out for “number one” rather than for his master’s interests, which was his assigned function. When the master uncovered the discrepancy, he naturally wanted to receive an accounting of the estate and to remove the steward from his position.

In response, the steward called in all the tenant farmers for whom he was holding promissory notes. What he did, apparently, was to cancel the inflated interest he’d tacked on—since he was no longer steward, he wouldn’t have gotten any of it anyway. He allowed the tenants to pay only what was just. He had them re-write their notes because it was he who had set the amounts to begin with.

As a slave, he was reduced from the highest possible status to the lowest. His hope was—since he still belonged to the master as part of his property—that the tenant farmers would appreciate what he’d done and provide him with some position—and sustenance—on their farms. No wonder the master commended him—he was rid of him, and he was no longer the master’s problem!

Remember that a parable is different from a fable that would have a moral or a punchline. You’re meant to walk away from a parable wondering what the deeper meaning might be. For the sake of the Greek Christians in the early Church who were familiar with fables, but not so much with parables, Luke and the other evangelists often tacked on known sayings of Jesus at the end of his parables to make them more understandable. There were four of those sayings tacked on to this parable, but I’ll leave it to you to review them. They’re sayings about the children of this world versus the children of the light, about making friends with dishonest wealth, about those who are trustworthy in small matters, and about serving two masters.

Now, what can we see in this parable? What’s our interpretation? What I see is metanoia—a change of heart. The crisis of being dismissed causes the steward to reinterpret what’s important in his life. He’s been embezzling from his master to feed the primary goal which was amassing wealth. Perhaps he was envious of his master’s lifestyle and wanted to emulate it. I wonder if he knew he was being dishonest, or did he justify his behavior because he could get away with it?

We humans are extremely adept at self-deception. Our egos can rationalize away committing the most horrendous atrocities. Some people in every war become involved in the most inhumane actions imaginable, and yet are capable of justifying their actions at the time and even afterwards. We can look around us at those perpetrating rampant prejudice and injustice in our own countries and communities to see just how powerful self-delusion can be. For the steward in the gospel, eventually hard reality came knocking and his value system was turned on its head. Suddenly, his rationalized behavior had real-life consequences.

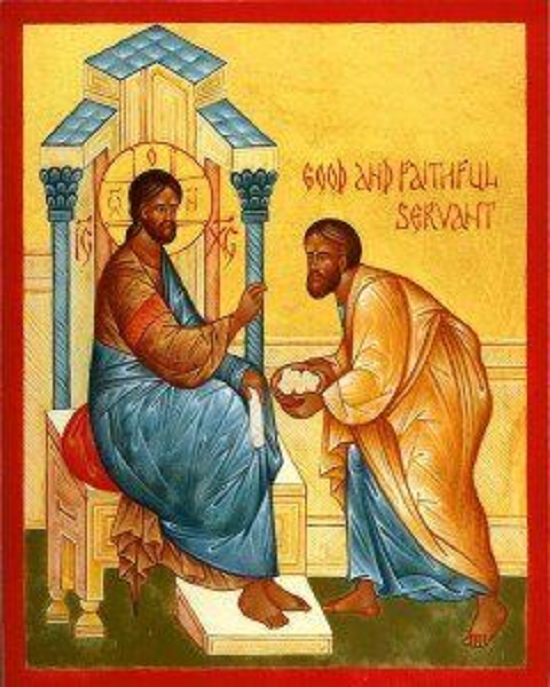

The gospel story threatens that, like for the steward, sooner or later, an accounting will be demanded. Sooner or later, there ought to be a change of heart. The parable reminds us that it’s a whole lot easier to have that change of heart—to do an accounting of our stewardship—now, before it’s too late and we have to face the consequences of our actions. What kinds of stewards are we? How are we caring for the world we’ve been entrusted with. Are we exploiting it for our own egos and aggrandizement? Or, are we making sure that we’re carefully managing our responsibilities to God, to our neighbors, and to our environment?

God doesn’t punish, but the results of our unjust thoughts, words, and deeds carry with them consequences. Let’s not be like the unjust steward who had to receive a rude awakening before he had a change of heart. Our change of heart can be now and any time we remember that we’re not masters of God’s creation. We are but trusted stewards who, someday, sooner or later, will be called on to give an accounting of our stewardship.

Get articles from H. Les Brown delivered to your email inbox.