Scripture Readings

Just because today’s gospel is familiar—the Beatitudes—that doesn’t mean we have nothing to learn from it. Hearing it read a thousand times doesn’t bring it any closer to our hearts. To begin with, let’s consider some of the background to the text. Apparently, the Beatitudes have a close connection to the actual words of Jesus. Scripture scholars have speculated that some scribe copied down Jesus’s words in his original Aramaic language, perhaps shortly after he spoke them. If that’s true, then both Matthew and Luke could have had access to it. From there, the gospel writers arranged the words to reflect their different approaches to the gospel message.

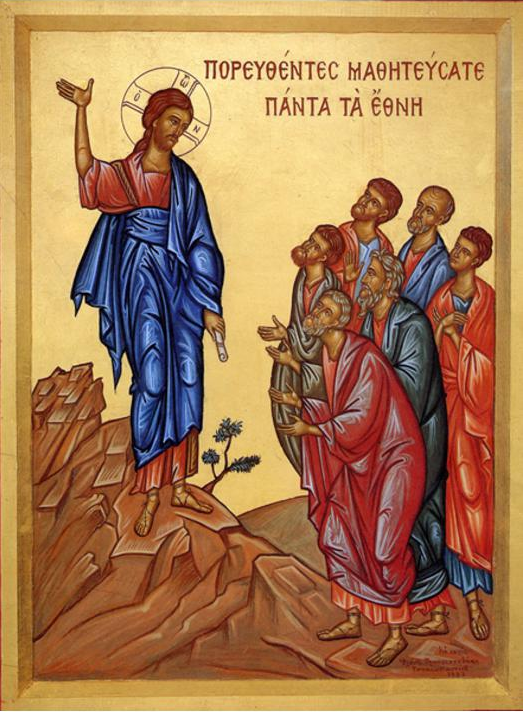

In Matthew, Jesus takes his disciples with him up a mountain. There is inescapable parallelism between Jesus on the mountain and Moses. The mountain is where Jesus goes to commune with the Father. In this case, he takes certain of his disciples with him. There, he instructs them in right judgment—seeing things not as humanity sees them, but as God does. In Mathhew, Jesus continues instructing his disciples with the Sermon on the Mount, providing them with a sort of manifesto of the gospel message. In Matthew, Jesus eclipses the Law of Moses with his teaching.

Luke takes a much different approach. Instead of going up the mountain with his disciples, Jesus comes down the mountain with his chosen Twelve. His audience here includes not only his disciples, and not only Jews from Jerusalem and Judea, but a rag-tag bunch of foreigners and others—just the kind of diverse following you might expect to find following Jesus out of curiosity. For Luke, Jesus’s discourse goes beyond instruction. He speaks directly to the dispossessed in the crowd—the poor and ill, the hungry, the mourning, and the despised. Luke’s Beatitudes are words of consolation that Jesus carries down with him from his communion with the Father on the mountain.

That’s some of the background. Now, let’s look at the text. Our language lesson today will focus on the word translated as ‘blessed.’ The word ‘blessed’ can be used to translate two Hebrew words. One is ברוך (baruk) and it is used in a liturgical sense, referring to God’s holiness. The other is אשר (asher) which is the condition of happiness and contentment. When these are translated into the Greek, we find the same distinction. Ευλογομενος (eulogomenos) is used for God’s blessing. Μακαριος (makarios) is used to translate the word for happiness and contentment. The word Luke uses here is makarios—happiness. In other words, in no way are Luke and his source, Jesus, suggesting that misery is a blessing from God.

To whom is Jesus addressing these words of consolation? First of all, the poor. These are the πτωχοι (ptokoi)—the timorous bunnies—the אנוים (anawim)—God’s little ones. Then, there are the hungry—the needy who lack life’s essentials. Then the weeping—those who have lost something or someone important to them. And, finally, the despised, the disrespected, those whose good name and reputation have been trashed. These were the kinds of people who stood in the crowd listening to Jesus.

Why do you think Jesus would urge these people to be happy and content? Was Karl Marx right when he wrote that “religion is the opiate of the masses?” Not at all. We can better understand what Jesus was talking about if we look at those to whom he said, “Woe!” They are the rich who are self-sufficient, the satiated who have had all their needs met and then some, the players whose lives are full, and those enjoying fame and popularity. Why were these people singled out?

It has to do with self-reliance. The self-reliant court disaster. They are people who either have never learned or have forgotten the fundamental lesson of spirituality. That lesson is our radical and total dependence on the grace and power of God. A spiritually mature person is one who has stared into the abyss and know in their bones that nothing of their own doing was able to save them. It’s the message of the cross and reason why Christianity is a religion for adults. There’s no place for self-congratulation in the Resurrection, just as there’s no room for gratitude in the self-reliant.

The poor, the hungry, the sorrowing, and the despised can find consolation in their capacity to appreciate their absolute dependence on God. That’s all that’s necessary to allow God’s grace and power to work, in them.

I’ve always believed in God. But I have to admit that, for much of my life, God was what Nietzsche called a “stopgap” to be relied on when all else failed. How often I said, in effect, “Thanks, God. I’ll take it from here. I’ve got this.” That kind of “thanks, God” is pretty much an empty phrase—an empty eucharist—because it springs from self-reliance. I might as well have said, “Thanks, but no thanks.” It’s only when my self-reliance could carry me no further and I got to experience my own powerlessness that I became an anawim. I became hungry. I wept. My self-image went to nothing. When that happened, there was nothing left to do but surrender. Out of that, came an experience of God’s grace and the serenity, peace, and happiness that flowed from it. More importantly, out of that came an overwhelming sense of gratitude—of eucharist—that carries me still. Today, I live my life in gratitude because I owe everything to the Power greater than myself.

There’s the lesson in today’s gospel: when you can ignore the empty promises of self-reliance and embrace your spiritual condition—however desperate it may be—trusting in the enduring love of God, blessed are you.

Get articles from H. Les Brown delivered to your email inbox.