Scripture Readings

Last week, our friend Gary asked an interesting question in a comment he left on one of the homilies I had posted on my website. He asked whether behavior shouldn’t be taken into consideration when evaluating sin. It’s a good question, because that’s the way all of us—and Christians everywhere—have been taught to think of sin. We want to know, “What did you do?” But is that the way Jesus thought of sin? The answer to that question can be found in the parable in today’s gospel.

Pay attention to the background. Tax collectors and sinners were coming to Jesus to listen to him. They even dined with him. When the scribes and Pharisees saw that, they were scandalized. Tax collectors were Jewish agents of the Roman occupation, taking money from their own people on behalf of the pagan enemy. They were also known as thieves, collecting considerably more than what they were owed, and pocketing the difference. Sinners were those Jews who flaunted the Law of Moses, not just with their sexual behavior, but also by ignoring the laws of purity and their religious obligations, like the observance of the Sabbath. Some were ignorant of the Law, others disobeyed deliberately.

In contrast, the scribes were experts in reading and interpreting the Law, while the Pharisees were experts in observing it down to the minutest detail. The scribes and Pharisees taught that sinners—those who disregarded the Law—should be shunned. To break bread with these people—in effect, to have communion with them—was unthinkable. Sinners’ behavior was unforgivable in a system where conformity to the Law was paramount.

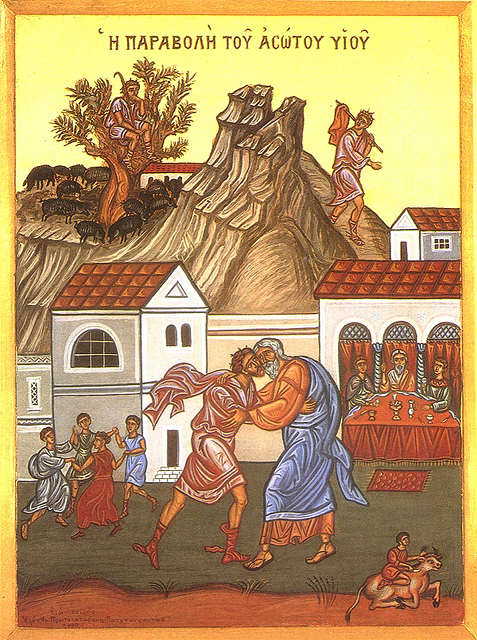

The gospel story today is a parable, not an allegory. With a parable, listeners are invited to meditate on the characters and events portrayed, rather than try to figure out whom or what each character represents. In the parable, there are obviously three main characters: the father, the younger son, and the older son. It was a common practice at that time for a wealthy father to distribute his property to his adult heirs while living, rather than at death. That’s why the younger son asked for his share of the inheritance.

Consider this: in many cases, the eldest son would be the sole heir in order to keep the property and wealth together in the family. Yet, the father was generous to his younger son, and gave him a portion of his estate. Note that the estate was given him without reservation. There were no conditions put on the gift and no stipulations. If the father had any qualms about how the son would handle his inheritance, it did not factor into the gift.

As for the younger son, he saw only opportunity in his inheritance. He didn’t recognize or appreciate the responsibilities that come with a gift of that kind. For, “to whom much has been given, much will be required.” [Luke 12:48] So, he took advantage. He squandered it. The Greek word translated for us as “dissipation” means a combination of unbridled sensuality and extravagance. This is much more serious than a simple failure to live up the letter of the Law. Anyone listening would have to agree that it was reprehensible behavior.

To spend extravagantly without consideration of the consequences exposes a person to those very consequences. Neither the father, nor anyone else punished the boy. Just as virtue is its own reward, so vice carries with it its own punishment. What defines bad behavior is the inescapable set of consequences built into it. We can’t help but relate this to God. God neither punishes bad behavior, nor does he shield us from its consequences.

Just as the punishment is contained in the behavior, so is the remedy. When at last the boy is deprived of every distraction, what’s left is the memory of his father’s loving kindness. Despite what he says about his father’s servants having more than enough, that’s not what motivates the boy. What draws him back to his father is the memory of his father’s love and the hope that his love for him is not exhausted. His whole appreciation for life has shifted from his own material well-being to a recognition of the value of spiritual realities like the bond of his father’s love. That’s what draws him back home.

I’ve often heard it said that this is not so much a parable of the prodigal son as the parable of the prodigal father. His love for the boy is undiminished by the boy’s behavior. He doesn’t ask his son what happened. He doesn’t ask where his property went. He doesn’t call for an accounting of the boy’s behavior. The father’s love is conditioned on none of these things. It’s their relationship that matters to him—their spiritual bond. He must have realized that their relationship had been threatened by the boy’s self-centeredness. Yet he knew that he couldn’t force the boy to love him as he loved his son. The boy had to lose everything before the value of that relationship became clear to him. When he let him go, did the father understand that he might never recover his son’s love? Of course. But he never lost hope.

Now, let’s turn to the older boy. What’s going on there? What’s he feeling? His principal feeling is resentment. Why? On one hand, he feels superior to his brother because of his own stellar behavior. However, behind that behavior lay the bitter feeling of being put-upon by his father. He feels like he’s done what his father asked, even though it was an imposition. He did what he did out of a sense of obligation, not out of love, or even gratitude. He counted the cost of his obedience. He considered not that he’d been gifted by his father, but that the father owed him for what he’d done “for him.” As a result, his resentment turned to jealousy and he spoke rudely to his father, was petulant and arrogant. His behavior may have been outwardly correct, but he missed the whole point.

Which boy was the true sinner: the one who faced his own character defects, had a change of heart, and returned to his father with genuine humility and gratitude, or the one who was arrogant and entitled, blind to both his own self-centeredness and his father’s love? Sin, after all, is not an action but a condition of the heart and soul. What appears as bad behavior is not a sign of vice, nor is good behavior a sign of virtue.

We know that Jesus told this parable as a lesson on hope to his fallible listeners—those who had gathered around his table to hear him—and as a critique of the arrogant entitlement of the scribes and Pharisees. But which group did Jesus himself identify with? The answer is in the parable itself: “…this son of mine was dead and has come to life again; he was lost and has been found.” There is an unmistakable echo there of Christ’s suffering and death in identification with sinful humanity. As Saint Paul writes in today’s second reading, “For our sake, he made him to be sin who did not know sin…” And there is the promise of the resurrection for those whose hearts are broken, because Christ rose from the dead not just for himself, but also as “the firstfruits of those who have fallen asleep.” [1 Corinthians 15:20] If our heavenly Father rejoices over the resurrection of his Son, so will he celebrate over us, the Body of Christ, “for we were dead and have come to life again, were lost and are found.”

Get articles from H. Les Brown delivered to your email inbox.