Reflections on Sexuality and Spirituality

Until we can overcome the false dichotomy that lies at the root of the human psyche, we will never experience genuine spirituality. The problem lies not so much in our thinking, but in the interpretation of our perceptions. Our minds are essentially creative: drawing meaning out of a chaos of sensations. For the most part, we’re wholly unaware of how we digitize our analog reality; yet, even our language creates a black-and-white world where there exists only shades of gray.

Nothing could be more natural than to believe in a universe of opposites. We think only in those terms: day vs. night, animate vs. inanimate, alive vs. dead, hot vs. cold, smooth vs. rough, hard vs. soft, sweet vs. sour—we could go on endlessly. When we try to apply these interpretations to the realm of the spirit, we produce nonsense. We set spirit against body, good against evil, God against the devil.

When I first started to meditate, like most people, I tried first to get rid of the body (by ignoring it), then of the mind (by saying prayers or mantras). The concept of allowing the body and mind to just be in prayer was quite foreign and, like many people, I thought I wasn’t doing a good job when body and/or mind “intruded” into my meditation time. Keeping them quiet was a struggle.

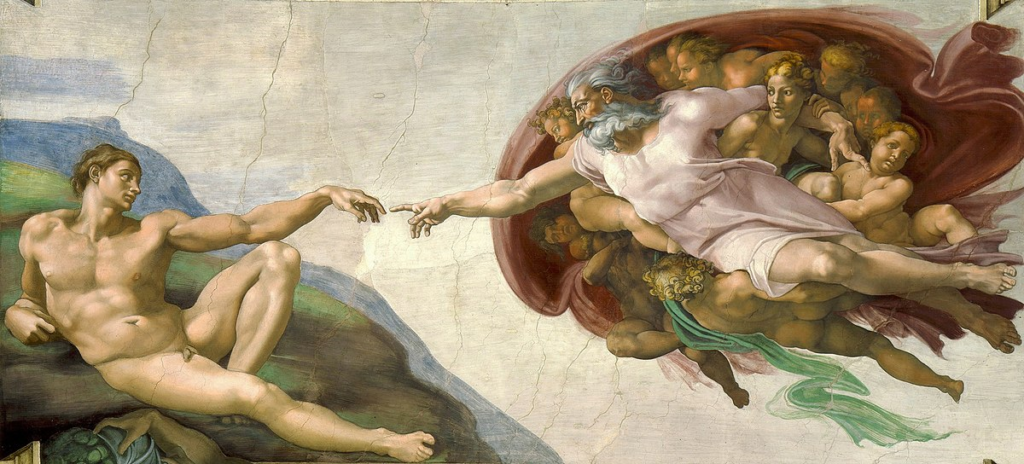

Where did our skewed dualist interpretation of reality (as we perceive it) come from? Is it purely an invention of our imagination, or might there be something behind it. In fact, duality arises out of the nature of God itself. If God exists at all (and if not, do we exist?), God must be All in All—devoid of dimensions, parts, or extension in space or time. Yet, by the very fact that we experience ourselves as being-in-the-world-with-others (Dasein: cf. Martin Heidegger, Being and Time) we experience “not-God.” Once we comprehend this, we must turn the concept of “creation” on its head. When we acknowledge God as creator, we must, by that fact, recognize God as source of negativity. Rather than “making something out of nothing,” the act of creating becomes the insertion of the “not” in the core of the undifferentiated unity that is God.

Rather than e pluribus, unum, creation must be seen as e uno, plures “out of One, many.” Yet, in it we perceive a mystic pull toward unity in an entropic universe. We internalize it as though the dynamic between dark energy (driving the universe to expand) and dark matter (drawing it together) is occurring within us. Our longing for unity—for wholeness—is undeniable and inescapable.

Crosby, Still, Nash, and Young sang about it in Woodstock: “I’m going to try an’ get my soul free. We are stardust. We are golden. And we’ve got to get ourselves back to the garden.” We have an innate longing to overcome the dualism—the fragmentation—that has infected our understanding of ourselves, our universe, and our God.

From its earliest days, Christianity has been infected with the dualist disease it inherited from Zoroastrianism through Manichaeism (light vs. dark, good vs. evil, body vs. spirit) via Augustine, and the distrust of the physical found in Judaism (clean and unclean). Although you’d never know it from the way it’s presented today, true Christianity is different from other belief systems. True Christianity is incarnational. “And the Word was made flesh.” [John 1:14]. It takes the resurrection seriously—not just of Jesus, but of all those fully alive in the Spirit. In other words, there is an understanding of the indissoluble unity of body-spirit. In this sense, the authentic Christian understanding of our place in the universe is closer to that of Hinduism or Buddhism than it is to the dualist Manichaean/Jansenist belief system that masquerades as Christianity today.

Prayer, then, needs to be a psycho-physical, even psycho-sexual experience. We do not come to God—however we imagine God—as disembodied spirits (ghosts). We bring our whole being, or none of it. When we pray, we strip ourselves naked before the great Mystery, not just mentally, or symbolically, but entirely. There is no machine apart from the ghost; but more importantly there is no ghost apart from the machine. The ghost in the machine is dead. The ghost IS the machine.