Scripture Readings

What’s going on in today’s gospel reading? Right at the beginning of Jesus’s public ministry, Luke takes us back to Nazareth, where Jesus grew up. Along with all the observant men of his village, Jesus goes to the local synagogue for Sabbath services. Although no one is absolutely certain of what those services were like, from what we know, they began with a couple of prayers—one was assuredly the Shema: “Hear, O Israel, the Lord is our God, the Lord is One.” Then, there were two Scripture readings, one from the Law (the Torah), and one from the prophets. That was followed by a homily, and the service was concluded by a priestly blessing, probably the familiar one from the book of Numbers [6:24-26], “The Lord bless you and keep you. The Lord let his face shine upon you and be gracious to you. The Lord look upon you kindly and give you peace.”

Does any of this sound familiar? It should because the Christian liturgy was adapted from that first century synagogue service.

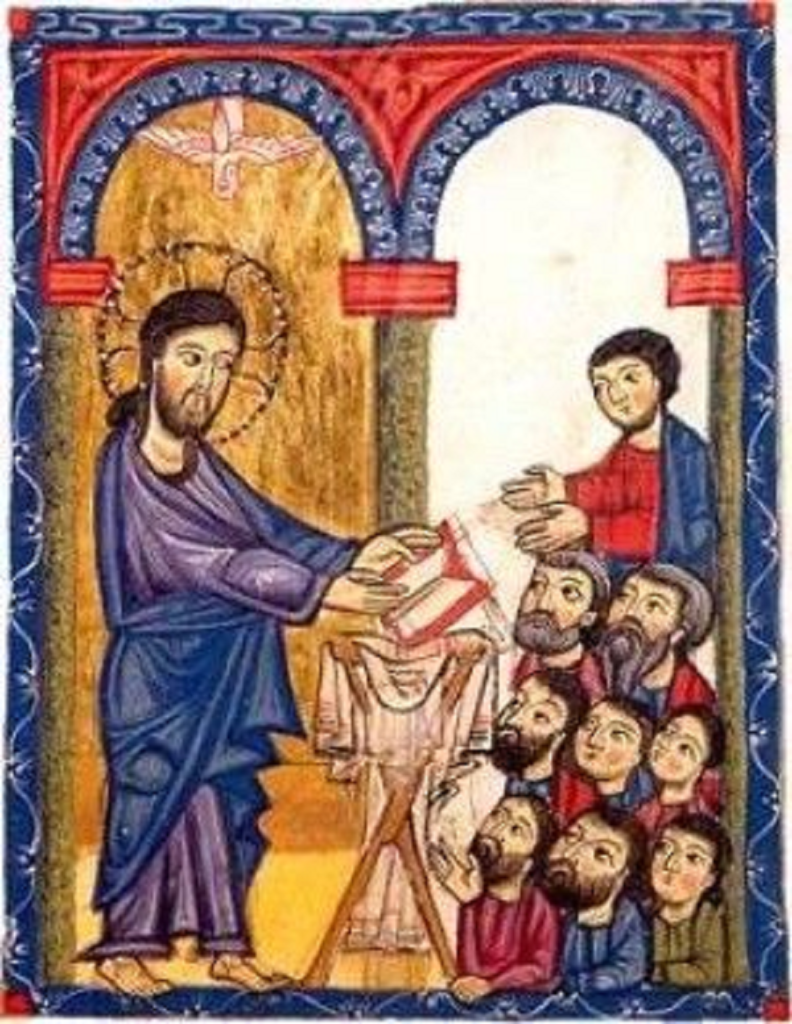

Notice that, in the synagogue, there were no priests. The role of priest was to offer sacrifice in the Temple in Jerusalem. The synagogue was a more egalitarian and democratic institution. It was led by a man elected from the community, and any teacher—or rabbi—could be called on to take part in the service. Since Jesus was acknowledged as a teacher, as an honored guest at his home synagogue, he was invited to read one or both readings and comment on them. From this, we can deduce that Jesus must have spent his youth and young adulthood learning to read and interpret both the Scriptures and the Jewish religious traditions.

Luke reports that, when Jesus was asked to read and interpret one of the Scripture passages, he chose one from the Prophet Isaiah [61:1-2] that was quoted here. Other evangelists report that Jesus taught in the synagogue, but only Luke tells us which passage he commented on at this occasion. To understand better what Jesus meant by this teaching, it would help to know the context of what Isaiah was referring to.

When people heard this passage, they probably understood it to refer to the jubilee year that’s prescribed in the Book of Leviticus [25:8-53]. Here’s what it says [25:10] about the jubilee that must occur every forty-nine years: “…you shall make [it] sacred by proclaiming liberty in the land for all its inhabitants. It shall be a jubilee for you, when every one of you shall return to his own property, every one to his family estate.” The passage goes on to describe a massive “reset,” where all property must return to its original owner, all debts must be cancelled, and all Jewish servants and slaves must be released from their bonds. According to Leviticus, all property belongs to the Lord, and it must return every forty-nine years to those to whom the Lord loaned it. We humans cannot claim “ownership” of our planet. It was here before us and, in one state or another, will be here after we’re all gone. In the meantime, we are only caretakers for Him who provided it to us for our use.

Jesus’s homily—as reported by Luke—was very brief. “Today this Scripture passage is fulfilled in your hearing.” We can only imagine how those who heard it reacted. Jesus clearly claimed that the one anointed by the Spirit of God and sent to bring about the restoration of all things was there in their midst. He was, in effect, proclaiming a permanent jubilee. And, in light of the Spirit overshadowing him at his baptism, he was the one who was bringing this about. In a sense, the whole rest of Jesus’s ministry was the embodiment of this passage.

I’ve mentioned before, in other homilies, that Luke’s writings, both his Gospel and his Acts of the Apostles, are focused on the Holy Spirit. They are either the prelude to Pentecost or commentary on it. For Luke, the words of Isaiah, “The Spirit of the Lord is upon me because he has anointed me,” do not refer to Jesus alone. They include us. Jesus’s life, death, and resurrection lead to the gift of eternal life in the Spirit for those who believe. The Spirit is the soul of the Church. We, too, have been anointed, consecrated, and sent to the humble of heart to proclaim liberty, healing, release, and the enduring love of God. This is our commission as Christians. This is our commission as a Church.

So, how’re we doing? Our actions as a Christian community speak much more loudly than our words. What glad tidings do we bring to the poor, the anawim? Once again, let’s be specific. The word that the Septuagint uses to translate the word ענוים (anawim)—the word quoted by Luke—is πτωξ (ptox). It means, literally, people who are like little bunny rabbits. It’s the kind of thing poet Robbie Burns was talking about in his poem, “To a Mouse,” when he wrote, “Wee sleek’d, cow’rin’, tim’rous, beastie.” Those are they to whom the good news is to be proclaimed. Now, if God were giving out report cards to the Christian churches, what grade do you think he’d give to our institutions, based on their treatment of the timorous, the fearful, the dispossessed, the powerless, the outcast, the lonely, the despised, the condemned, the spiritually homeless? How will these people hear their jubilee proclaimed? How will we, because there, but for the grace of God, go I?

More to the point, as Christians, what can we do about it? As Saint Paul wrote in today’s second reading from his first letter to the Corinthians, we’re all given different gifts. We’re not all called to stand up and preach. We’re not all called to be social activists. We’re not all called to be confrontational. We are called, however, to live as though everyone we encounter is worth of love and respect. We are called, by our actions, to show God’s loving care to everyone, no matter how timorous, no matter how captive, no matter how blind, no matter how oppressed. That’s our proclamation. That’s our commission. That’s who we’ve been anointed by the Holy Spirit to become.

Get articles from H. Les Brown delivered to your email inbox.